During Black History Month this year, we’ve run a series of posts looking at African American leaders in both the past and present. Our final entry focuses on black Minnesotans’ fights for freedom — both for themselves, and others.

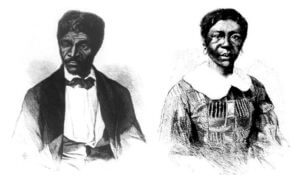

Harriet and Dred Scott

“Slavery lives in this country not because of any paper Constitution, but in the moral blindness of the American people, who persuade themselves that they are safe, though the rights of others may be struck down.”

Frederick Douglass on the Dred Scott Decision, 1857

Not everyone knows it, but Fort Snelling featured in the infamous 1857 U.S. Supreme Court ruling against Harriet and Dred Scott. Slavery infected all of America, and Minnesota is not an exception.

Army officers stationed at Fort Snelling frequently brought slaves with them, despite the Missouri Compromise banning slavery in the territory. Harriet and Dred met, and married, at Fort Snelling, before returning to Missouri. Years later they each submitted claims for freedom, stating their residence at Fort Snelling and elsewhere had emancipated them.

Their separate claims became Dred Scott vs. Sanford, and the U.S. Supreme Court’s controversial decision against their family’s freedom deepened tensions and catapulted the nation into the American Civil War.

Ujamaa Place & Otis Zanders

“Trust is important because these young men see themselves as being discarded by society. They have an ‘us vs. them’ mentality, and we have to change that.”

Otis Zanders, Ujamaa Place CEO, 2013

150 years after the end of slavery, freedom is still an issue for many black Minnesotans. The United States incarcerates more people than anywhere else in the world, and in 2013 African American men in Minnesota were 23 times more likely to go to prison than white men.

Ujamaa Place is a local nonprofit dedicated to young African American men who face barriers to success – chiefly, previous incarceration. Ujamaa means “extended family” in Swahili, and that concept sits at the organization’s core: it facilitates community among its participants, helping them build strong connections and a network of role models and support.

CEO Otis Zanders worked with the Minnesota Department of Corrections for 34 years, and knows many of the pitfalls. He speaks passionately of empowering participants to take their lives back, and emphasizes the importance of re-establishing trust in community. He sees the participants’ work as a runaway transformation, into “a positive influence on this block, this street, this community and this city.” Mr. Zanders was a 2018 recipient of the Saint Paul & Minnesota Foundation’s Facing Race Award for his anti-racism activism.

Ujamaa Place’s work continues, with clear results: In its first three years the organization served 200 men, and only saw one return to prison.